It is a great privilege to be here today and have the opportunity to deliver this address on Advocacy and Policies.

Considering the amazing amount of institutional knowledge in the room, the best way I can meaningfully contribute to the conversation is by bringing to the table my experience from “the ground.”

Over the past fifteen years I have been working as an independent researcher supporting artists, cultural practices and productions in countries in conflict. For me, it is hardly possible to think of cultural heritage without thinking of people first.

I would like to begin by showing you a short art film from Afghanistan.

The film, directed by Farahnaz Yusufi, is titled Ruyeeha-e Parihaa which in Farsi means Angel’s Dream.

There is not much to add to such a testament to the power of ingenuity. Farahnaz Yusufi opens for us a window to the never-ending quest for poetry. In the film, she also makes a complex reference to Sufi mystical culture that I have no time to unpack now, but we can certainly return to later in the discussion. Works like this, which combine a multiplicity of emotional, cultural and symbolic layers, interpellate us – as professionals who work towards the protection, preservation and revival of cultural heritage – with many fundamental questions. These questions, rather than the answers to them, will be the fil rouge that will guide my presentation.

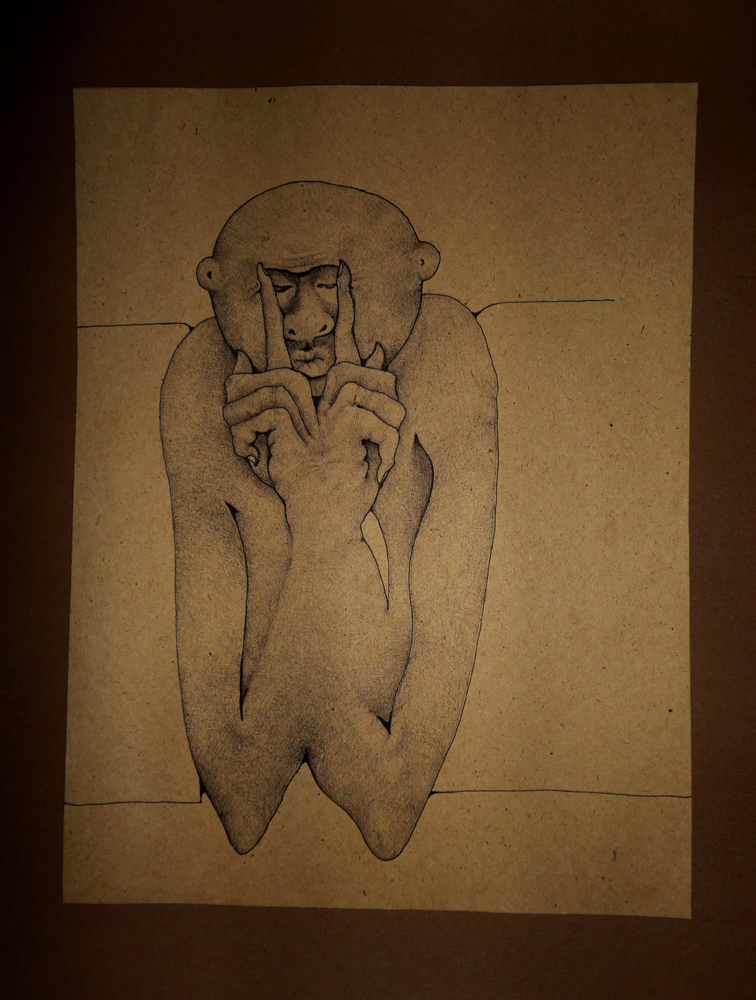

Baqer Ahmedi, Silent Face, 2014

A few days ago I met up with Baqer Ahmedi, one of the most talented emerging artists in Afghanistan, whom I have had the pleasure to mentor since he started his artistic journey. He updated me about his work and told me that he was not entirely satisfied with the progress he was making: for several months he could not draw as he had ran out of wasli paper and there wasn’t any available to buy in Kabul. Baqer Ahmedi is a contemporary artist, who works on a kind of handmade paper called wasli that is traditionally used for miniature painting – you can see here a couple of images from his work.

Baqer is about to leave Afghanistan as many artists have done before him. He’s going to Pakistan in a couple of weeks to begin his bachelor’s degree in Lahore. There he will be able to buy more paper and resume drawing. His matter of fact tone in telling this story stayed with me: there was no resentment. This is how often things are there in Afghanistan; it is normal not to have paper and not to be able to draw: there’s not much else to add.

It is from this lack of paper that we should probably start when we think of our role in protecting and reviving cultural heritage.

Luckily not the whole world is experiencing the same extreme conditions of Afghanistan, but I believe there’s much to learn from situations of conflict. I have just come back from Kabul, where I have been based for the past five years. In spite of the immense problems that the country is facing to shape itself into a mature and diverse nationstate, it is absolutely remarkable to see the relevance and centrality that culture and heritage play in the political debate.

During the last year, as a programme specialist with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, I worked closely with the Afghan Minister of Information and Culture to design a roadmap for both a National Cultural Policy and for the National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage. The challenges have been and still are enormous. I would like to share some thoughts on my experience and perhaps we can further discuss them in our roundtable later on.

Working at the crossroad between international organisations, funding agencies and public institutions requires a lot of juggling. There are petty power games, there is the pressure to show progress and present deliverables, there is the aspiration to be relevant, to be accurate, to be meaningful. It is a jigsaw made of tons of tiny moving pieces: each of them requires full attention as the puzzle needs them all in order to be complete. Any attempt at cutting corners simply backfires. The greatest dilemma is between the urge to be efficient and the ethical desire to be sustainable.

Here the biggest variables are “the people” and time.

Because of my personal political history, I have always distrusted top-down decisions. This attitude has a profound influence on how I conceive my work. More on this later.

To go back to the issue of “the people” and time, when working in the context of so-called developing countries, our activities are measured by the strict sets of deadlines dictated by donors’ fundings. It is the logic of projects that orientates us along with the requirement to show short-term tangible results matched against large, sustained financial investments. This is all well and good, but it is also extremely easy to lose perspective and forget the big picture.

Most of what I do is to work with people, but working with people requires time and the kind of time that is needed to gain trust and build an equal relationship is out of sync with the temporality of a project-driven modality.

Let’s think of the National Cultural Policy for Afghanistan as an example. The quickest I could envision a roadmap for its development was on a three year scale with at least two rounds of nation-wide consultation with civil society organisations, local elders, religious and community leaders. In a country like Afghanistan, though, even three years into the future are difficult to envision: hardly any donor engages in such a “longterm” commitment, many of the decisions are personality-driven and so directions change along with the high turnover of the people in charge. Moreover, from next April the new electoral season will begin and the uncertainty that this entails may discourage anyone to engage in anything that at this point would appear utterly impossible.

I do not intend to paint a hopeless scenario here, I am rather trying to think out loud about the rationale that is behind what may seem a more pragmatic and certainly faster approach, whereby experts are brought into the picture for short-term consultancies to give answers and supposedly solve problems. Not always, however, is the specific professional competence of these experts paired with a nuanced understanding of the complexity and uniqueness of the context.

This way of working raises a number of questions. Will this ever be impactful? Will the results ever last? Will people ever feel ownership of any of the decisions made in such a detached manner?

The answer to this lack of space and time is often found in advocacy. An unavoidable component of every project proposal, it becomes the way to reach out to the people, to involve them, to make sure that we tick the box of inclusiveness.

In this sense, the idea of advocacy is often mistaken with public campaigning, with large scale mobilisations that bring attention to pressing issues. By doing this, we hope to inculcate new ideas, to communicate to the people the urgency of concentrating our efforts for the preservation of physical and intangible heritage. Besides actions taken within the institutional framework, there are also special events that serve the same purpose.

Here are a couple of examples of individual initiatives that have quite successfully brought to the public attention elements of endangered cultural heritage.

In 2015, Zhang Xinyu and Liang Hong, two Chinese philanthropes, built in Bamiyan a 3D laser projector to create a 50-meter-tall hologram of the Buddhas that were destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban. This hologram was presented in a public event where 150 people participated.

Another beautiful example is the “before and after” series of photographs that Joseph Eid took in 2016 in Palmyra.

Joseph Eid/Getty

Expressions like these are significant examples of advocacy, but I believe it is important to think beyond them. Don’t get me wrong, I am not against campaigning and public mobilisation. I am however suspicious of an approach to advocacy that is limited to that. In these terms, in fact, advocacy becomes a tactic, almost a quick fix instead of a form of strategy.

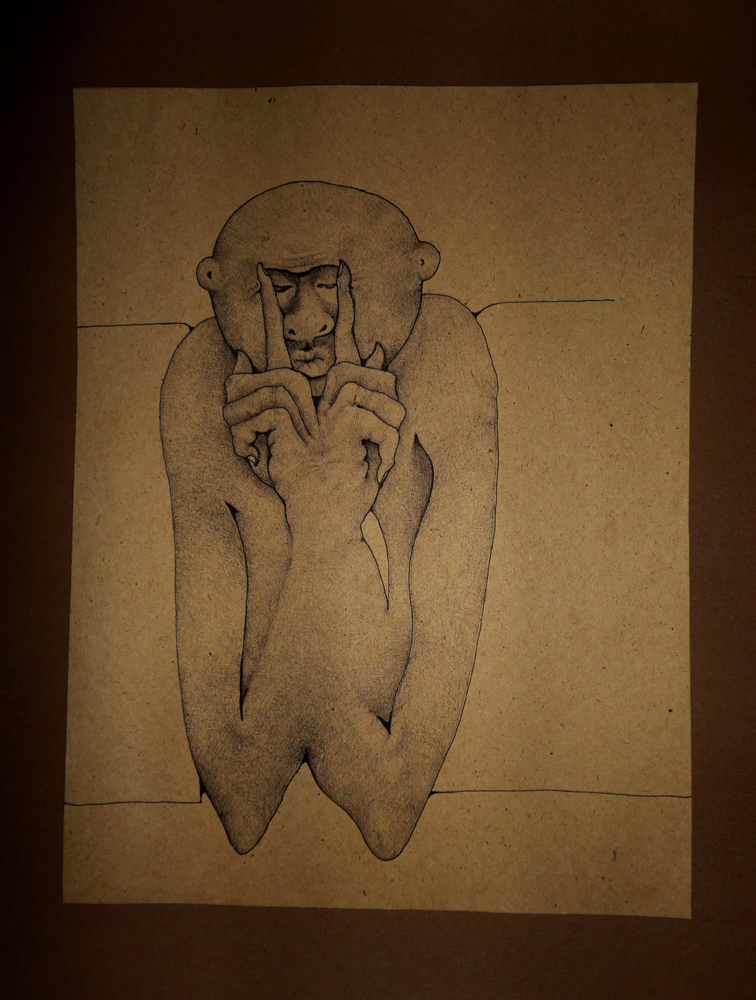

I just finished reading a book by Italian psychoanalyst Massimo Recalcati titled L’ora di Lezione. Per un’erotica dell’insegnamento.

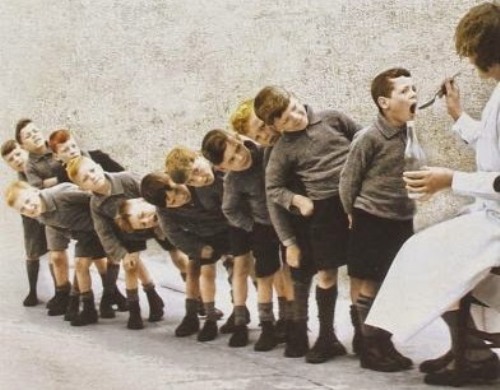

Massimo Recalcati, L’ora di lezione. Per un’erotica dell’insegnamento. Cover Photo.

There is no English translation of the book yet, the title roughly means The Lesson’s Hour. For an Erotic Approach to Teaching. The book addresses the profound crisis that the Italian school system is undergoing. It looks at how the great social transformations of the last four decades have had an impact on School (with capital S) as an institution as well as on the role that teachers play in the educational enterprise. This is not the right time to go into further detail about the book, but there is one point that Recalcati makes that may be useful for our discussion. He believes that teachers should reclaim their role in presenting to the students the objects of knowledge as erotic objects. In other words, the task of the teacher is to activate the desire to know. In Socratic terms, this is an unearthing process rather than an imposition. The maieutic art of teaching recognises potentials, nurtures desire and facilitates the space of expression.

I wonder if we can use the same model and re-think of advocacy in such terms. This will require, however, a serious shift in attitude.

A few weeks ago, I gave a talk at a gathering of geographers and GIS experts in Bangalore in South India on the role that mapping can play in heritage preservation. Most of the participants came from a non proprietary OpenStreetMap (and a free software) background and the discussion that followed ended up focussing on the possibility of communities’ involvement and participation in the identification and geo-localisation of heritage sites. At this point a member of the audience, the only urban planner in the room, stood up and quite forcefully stated that people don’t know what is relevant; it is therefore our duty to teach them the importance of heritage. She left the room soon after, but the echo of her statement informed the rest of the conversation.

The presumption that we, all of us in a position of power and responsibility, know better than “the people” is a scary beast and it encages the nature of heritage within narrow and “managerial” parameters.

Statements like these are problematic at a multiplicity of different levels and they are – whether in a spoken or unspoken fashion – more common than one would be willing to admit. The first order of troubles comes from the fact that we (the experts, the bureaucrats, the academics) set ourselves apart from them, the people. We forget that beyond our expertise it is our cultural roots to make us who we are – be it by embracing or by opposing them. Somewhere, somehow, beyond our professional lives, we belong, we are members of a community and we are shaped and defined by a set of cultural practices, places and meanings that we share with others.

It is remarkable how quick we are in forgetting this when we wear our professional hats.

The second layer of problems with such statements comes from the fact that they ossify the idea of heritage within strict rules and regulations thereby ignoring its granular and embodied nature. In both physical and intangible terms, heritage is malleable and ever-changing, it is that particular tree, that folktale, this street corner that a community aggregates around and identifies with.

When my sister tells the story of where we come from, she loves to say that local dialects change every few kilometres and with every single village. What sets our hometown apart, she would go on, is the fact that we don’t have any distinctive dialect as the city was entirely destroyed by an earthquake in 1915.

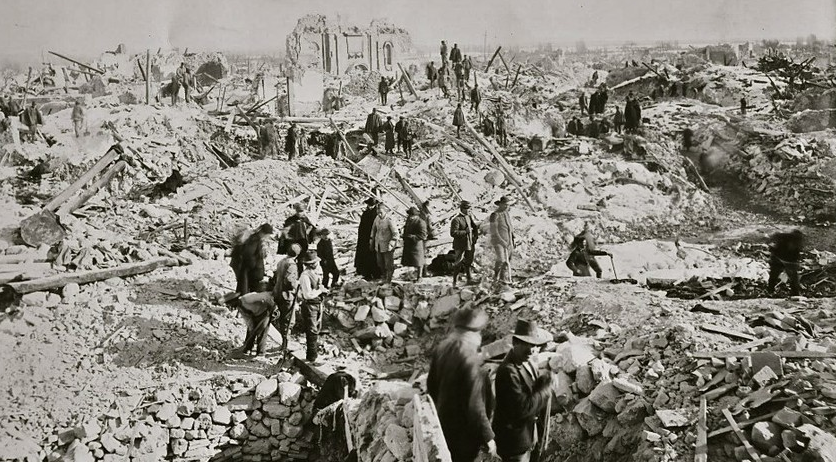

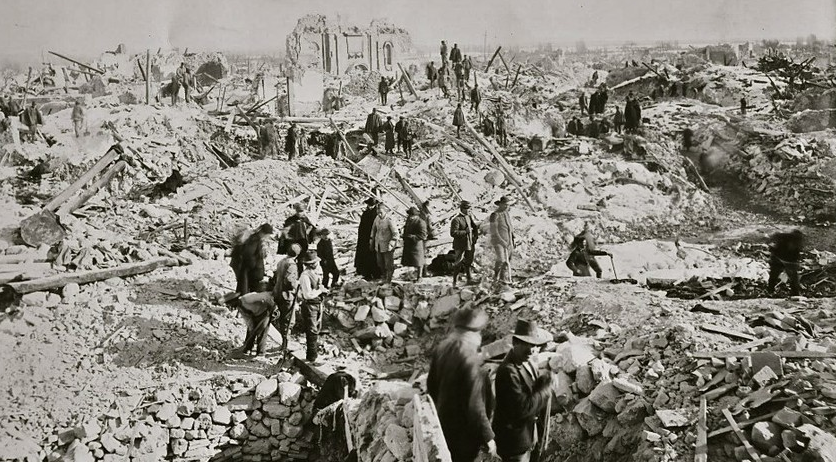

Photo by Lansing Callan for USGS (Us Geological Survey)

It is apocryphal stories like this one that help us shape our narratives as individuals who belong to a place and a community. It is stories like these that perpetuate a notion of living traditions.

I have recently discovered an incredibly inspiring document written under the auspices of UNESCO in 1998 in occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is the Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities, which quite simply responds to the rights we claim with a set of duties and responsibilities that we have in order for our rights to come alive.

The Declaration is a manifesto of the ethics of responsibility and helps us conceiving the shift between moral and legal duties: it is about what we ought to do in order to guarantee the survival of the universal democratic values we cherish and claim as fundamental.

The strive towards equality and meaningful participation in public affairs is at the core of the document.

Relevant to our context, Chapter 11 of the Declaration is dedicated to Education, Art and Culture. Within this section, article 38 reminds us that within communities there is both an individual and a collective responsibility to provide a framework for and to foster arts and culture.

It is on this note that I want to conclude my address today.

As professionals who work towards the preservation of heritage – as well as as individuals who belong to a particular community – our job is also our duty.

When we create the conditions for the protection and the full enjoyment of cultural heritage we are basically performing our civic, obligatory and reciprocal duty as citizens.