This text was originally published on Kashmir Reader on the 6th of May 2016

Indian-occupied Kashmir is one of the most densely militarised corners of the world even though it is not officially a country at war. With over half a million troops stationed within its boundaries, the ratio between Indian armed forces and Kashmiri civilians is even higher than that between foreign military and civilian population at the peak of the American invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. Despite the promise of a plebiscite, the region has been denied the right of self-determination and has seen the criminalisation of organised forms of dissent. Movement is regulated and the right to public space curbed under the pretence of maintaining law and order. In such a climate, the struggle over the control and definition of territory assumes a fundamental role. Within this context, therefore, the management and articulation of heritage assume a loaded political meaning. Whose history is preserved and promoted? By whom and through which political allegiances? What messages and agendas are championed through heritage? What are the meanings and reasons for reclaiming cultural roots through fabricated notions of tradition?

After the 2008 and 2010 uprisings, the Indian government has associated systematic repressive violence with a renewed public discourse on the beauty of Kashmir – a pristine landscape devoid of people. To strengthen its propagandistic effectiveness, the central government started providing financial incentives to tourism and pilgrimages as devices to normalise the conflict. This whole political apparatus is mostly articulated in religious terms with an emphasis on the indivisible sacrality of Indian land since ancient pre-Islamic times. The same strategy is adopted in relation to the border, where Hindu shrines are installed within the premises or in the vicinity of Army check-posts. These newly established religious sites, which become collective yet segregated places of worship, indirectly sanction the Army’s presence as well as the quintessentially Hindu nature of India as a country.

In the decades that followed Partition, India and Pakistan sat at the negotiating table several times to try and solve, among other things, their disagreement over the management of Kashmir. These talks did not achieve much, but sanctioned the “question of Kashmir” as aterritorial dispute – an empty land on a map where the issue was how – rather than if – it should be divided.Almost seventy years and several UN resolutions later, the situation has not changed. The articulation of the discourse is still framed in bilateral terms and continues to exclude the political voice of Kashmiris. Through a narrative that reinforces the idea that the “solution” for Kashmir has to come from India and Pakistan, Kashmiris themselves are sidelined and not acknowledged as equal, let alone indispensable, interlocutors. It is the fate of the land that is at stake, not the fate of those who belong to it. This unchanged perspective perpetuates the legitimacy of a “mystical” tone whereby Kashmir has come to symbolise the unquestionable wholeness of India as a country.

The first months of 2016 have seen open and rampant tensions around the oneness of India. The central government and its supporters are undeterred in their attempt to promote such unity and reinstate the intrinsically religious nature of Indian nationalist loyalty founded on the centrality of the myth of Bharat Mata. The reinforcement of the identification of the Indian land with the body of the mother collapses political and religious categories, turns the nationalist struggle into a religious duty and charges political claims for self-determination with an almost blasphemous and hence seditious connotation. Incidentally, by reciting the Bharat Mata ki Jai, the Indian Army finds a religious justification to their brutality: their mission is to protect the integrity of the land thus turning into the uncontested custodians of a dominant interpretation of belonging and heritage.

In order to be able to grasp the complexity of the notion of heritage and the intertwining between the sacralisation of the land and a sense of belonging in Kashmir, it is fundamental to grasp the relevance of the events of the 1990s and the displacement of the Kashmiri Pandits. Much of their pledge has been in fact appropriated by a chauvinist nationalist agenda and their desire to return to their homeland has been manipulated to reinforce the Hindu nature of the wholeness of India.

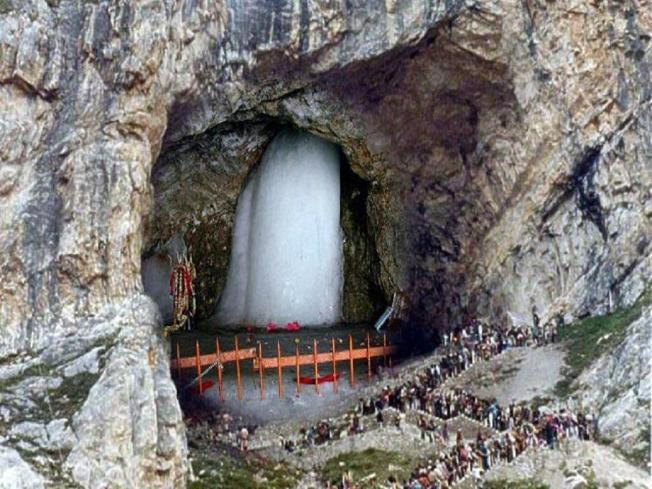

The recent revival of the Amarnath Yatra is an important example of how people’s mobilisation around cultural memorialisation can be used to interpret the political implications of the promotion of immaterial heritage. Located 140 kilometres North East of Srinagar, at an altitude of almost 4,000 meters, the cave of Amarnath, with its ice stalagmite, has been for centuries the site of religious pilgrimages. At the end of a steep climb in a pristine forest, the cave is blocked by snow for most of the year and it is only accessible for a short period of time during which pilgrims challenge altitude and asperities to pay their respect to the god. Legend has it that this is the secluded place that Lord Shiva chose to reveal to Parvati the secrets of immortality and of the creation of the Universe without being heard by any other living being. The cave is therefore revered and considered among the most important religious sites for Hindus. To corroborate its sacrality, it is believed that the ice stalagmite, which is thought to be waxing and waning in accordance to the moon cycles, is an embodiment of the Lingam, the phallic representation of Lord Shiva himself.

After being forgotten for centuries, the cave was “miraculously” rediscovered around the 1850s by Buta Malik, a wandering shepherd during the reign of Gulab Singh, the first Dogra ruler of Kashmir. The Maharaja was all too happy to encourage pilgrims to visit the site. Since its modern inception, the Yatra was a relatively small event that lasted no longer than fifteen days and included twenty to thirty thousand local Kashmiri Pandits. Between 1991 and 1995, the pilgrimage was suspended because of political instability; it was then resumed in 1996 after assurances by the militants that they would not harm the pilgrims. That year, however, a sudden change of weather and unexpected snowfall caused the death of more than 250 people. In response to this tragedy, the government decided to impose stricter regulations and set up the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB).

The institutionalisation of the pilgrimage and the definition of the religious pre-requisites for the eligibility for the SASB represent a momentous turning point in the significance, promotion and political connotation that the Amarnath Yatra has acquired. It is after this transition, in fact, that the Sangh Parivar has shown a proactive interest in the pilgrimage, radically changing the narrative around it, thus escalating the politicisation of the initiative and hence its divisive nature.

Historian Eric Hobsbawm defines the process of the invention of tradition as an intentional way of using material from the past to serve novel purposes. This perspective resonates with an interpretation of heritage as a contemporary cultural use of the past, thus highlighting its political dimension. Hobsbawm’s definition of “invented traditions” can provide a useful framework for the understanding of the shift in meaning and political significance of the Amarnath Yatra. Even though there is no academic analysis of the Yatra, the debate around it is quite heated at the level of civil society. Positions are deeply polarised and mostly see a split between the government bodies, militant Kashmiri Pandits and Hindus from mainland India on one side, and moderate Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri civil society organisations on the other.

Over the course of several interviews with Kashmiri Pandits living both in the Valley and outside it, it emerged that there was a shared agreement around the preposterous notion of “reclamation of Kashmir” utilised to justify the scale of mobilisation around the Amarnath Yatra. In a phone interview, S. – who spoke on the condition of anonymity as he feared that his positions would upset the community – told me: “Amarnath has no relation whatsoever with Kashmiri Pandits, we as a community have nothing to do with the shrine. Those who will tell you that the tradition is ours and Muslims are trying to destroy it, hold false and biased views that are fuelled by their anger at the displacement they underwent. This reactionary narrative is not inherent to Kashmir, it is the result of Indianisation and the media are contributing to exacerbating a narrative that is more important to Indians than it is to us.”

Sanjay Tickoo, a Kashmiri Pandit social activist, who decided not to leave his native Srinagar during the 1989 exodus and has lived in the Valley his entire life, highlighted the deep religious connection with nature in Kashmir that characterises the Pandits’ religiosity and framed the relation with the Amarnath Yatra in the same terms. He also expressed his discontent towards the fact that the pilgrimage was taken over “by those who claim to be the real custodians of Hinduism”. While dissenting from the interpretations of the Yatra as a form of political oppression, Tickoo criticised the composition of the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board where currently only one member, Bhajan Sopori, is a Kashmiri Pandit. He told me that this detail can be indicative of the politicisation of the pilgrimage and its disconnection from the Pandit community. Even though he did not seem too preoccupied with the implications of such adevelopment, his main concern had to do with the terrible environmental consequences the massive expansion of the Amarnath Yatra has caused over the years. He was highly critical of the great numbers and of the extension of the pilgrimage time from fifteen days to almost two months.

The effect that hundreds of thousands of people can have on a fragile mountainous environment is a general reason of concern. For many civil society activists, however, the ecological preoccupation is framed in broader political terms. Khurram Parvez, a member of the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS), lamented the detrimental effects that the Amarnath Yatra has on Kashmiri culture in terms of “its impact on our natural resources, its absolute lack of sustainability and the fact that it has become an alibi for an even further militarisation” Parvez was adamant in calling the Amarnath Yatra as a “military project run under the patronage of the State” and accused the SASB of being complicit with the State-sponsored narrative of reclaiming Kashmir.

As the BJP, RSS and other extreme right-wing Hindutva organisations appropriated the narrative around the Yatra, they started aggressive fundraising campaigns gathering large sums of money from diaspora Hindus across the world so as to be able to sponsor increasingly larger numbers of pilgrims entirely free of cost. This process changed dramatically the demography of the pilgrims who for the most joined the Yatra for opportunistic or ideological reasons. This tension is further heightened by the fact that pilgrims consider the Army to be there to protect them from aggressions by locals and terrorists alike, whereas for Kashmiris the military presence is an obvious disruption of their own lives.

Moreover, as the number of pilgrims grew exponentially, Kashmiri civil society organisations started denouncing the visible deterioration of the fragile Himalayan ecosystem around the cave. Scientific research shows the increase of waterborne diseases and water shortage in villages in South Kashmir during and in the immediate aftermaths of the pilgrimage. Yatris neither show any respect for the natural environment, by throwing all sorts of waste in the Lidder River and by defecating in the open, nor are they provided with the necessary facilities for a more considerate behaviour, despite it being one of the main tasks assigned to the SASB.

The tension between civil society organisations and the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board reached a peak in May-August 2008 after the state government granted the transfer of 40 acres of forest land to the SASB for the construction of temporary structures for the accommodation of pilgrims. The announcement that this would represent a permanent transfer created public outrage as Kashmiris saw the transaction as a blatant violation of article 370 of the Indian Constitution. One of the provisions of such article is that only citizens of the state can purchase and own land in the Valley. Khurram Parvez defined the land transfer and the plan to build on forest land permanent structures to host pilgrims as “an ecological disaster and yet other manifestation of the Indian occupation.” Street protests erupted across Kashmir and clashes between civilians and Indian Army determined the withdrawal of the transfer. This in turn triggered a wave of unrest in Jammu – where the majority of the population is Hindu – with Hindutva parties and organisations were up in arms calling for a comprehensive agitation to fight and take back the land of Kashmir defined as “the paternal property of Hindus”.

The 2015 Amarnath Yatra counted more than 350 thousand participants and several deaths. The 2016 edition is scheduled to begin on the 2nd of July and will last for 48 days. In an ostentatious attempt to regulate the Yatra, the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board announced that it will “only” allow 7,500 people per day on each of the two routes, therefore bringing the estimated attendance to 720,000 people. Violence and unrest are ebbing again in Kashmir following various episodes of brutal military responses to critical voices that dared questioning the indiscriminate acceptance of the oneness of India. In this climate, the forthcoming Amarnath Yatra may acquire further ideological connotations and be instrumentally used to serve chauvinistic Hindu nationalistic agendas. Leveraging on sentiments of belonging and the right to reclaim their own land through the construction of a well orchestrated invented tradition, the Amarnath Yatra is an important, if little known, example of the ways in which heritage movements can serve political purposes. Heritage activism in this particular case shows a dark and antagonistic side where the promotion of a carefully fabricated continuity to a selective sense of the past serves the Indian hegemonic discourse and indirectly legitimises both the presence of the Army and their deeds as custodians of the sacred unity of Bharat Mata.